In looking for something to fact check for this post, I went to Google News and searched “recent study” and happened upon an article from ABC News titled “Courtroom psychology tests may be unreliable, study finds“. The article describes a study published in the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest which reportedly found that courts are “not properly screening out unreliable psychological and IQ tests, allowing junk science to be used as evidence”. This study could mean that some evidence being used in trials might not actually be good evidence at all and could be swaying the jury toward verdicts that could lead to wrongful convictions of innocents. I will be fact checking this study and evaluating whether courts really are allowing unreliable tests and junk science to be permitted as evidence.

In looking for previous work, I searched DuckDuckGo for Politifact.com, Snopes.com, and FactCheck.org for a variety of search terms, including “courtroom psychology tests”, “courtroom psychology tests” in quotes, “courtroom psychology tests unreliable”, “psychological science in the public interest court tests” and “tess neal court psychology”. None of these returned any relevant pages from these sites, so I went on to Wikipedia. After searching “courtroom psychology tests”, I looked at the “Forensic psychology“, “Forensic developmental psychology“, and “Applied psychology” pages, but could only find one line in the first page saying that “Forensic psychologists routinely assess response bias or performance validity.” Thus, there seems to be little previous work on this subject, which makes sense as the study was only published on February 12, 2020.

Next, I tried to move upstream and find the actual study. By googling “Tess Neal courtroom psychology tests study psychological science in the public interest”, I was led to a New York Times article, which linked to a page from the Association for Psychological Science, who are responsible for the Psychological Science in the Public Interest journal, announcing the publishing of the study. I also found a page from the APS assessing the findings of the study. The announcement page linked to the PDF of the actual study. The first thing to note is the presence of many co-authors in the study who each have different qualifications and areas of study. Tess M.S. Neal works at the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University. Christopher Slobogin works at Vanderbilt University’s Law School. Michael J. Saks works at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and Department of Psychology at Arizona State University. David L. Faigman works at the Hastings College of the Law at University of California. Finally, Kurt F. Geisinger works at the Buros Center for Testing and College of Education and Human Sciences at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Thus, the authors of this study are coming at the study from both psychological and legal perspectives, covering both sides of the issue.

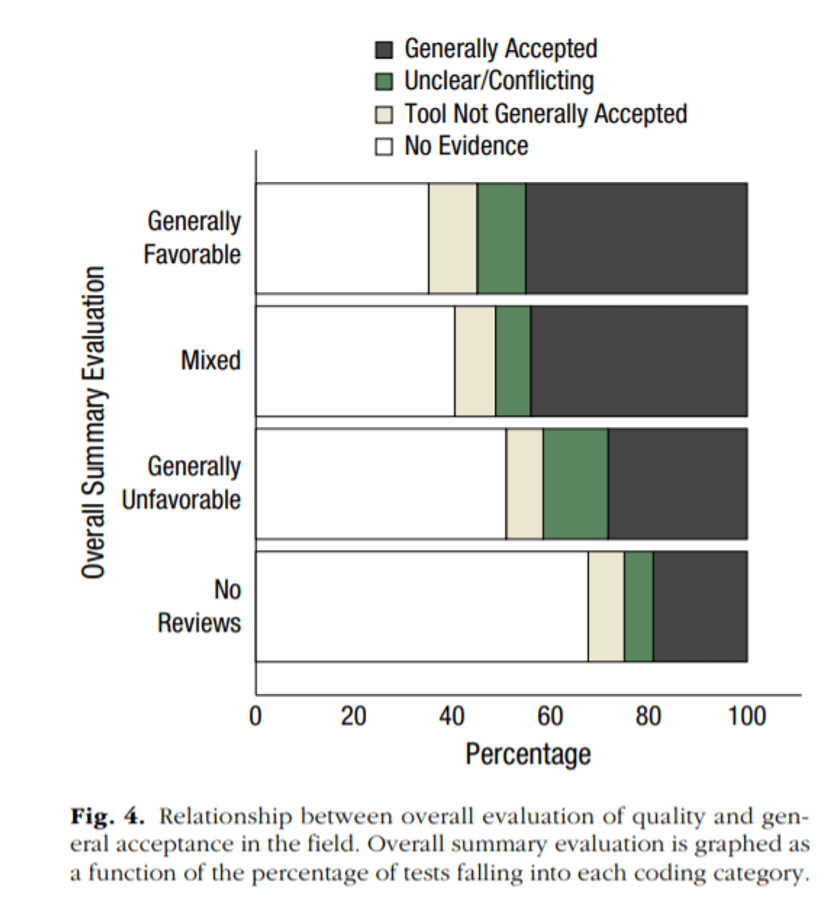

The study involved two aspects. First, they examined 364 different psychological tools used by “forensic mental health practitioners” who responded to 22 surveys, looking at how reliable the tools are and how much professionals question the tools. This part concluded that though 90% of psychological tools used in this context had undergone empirical testing, only 67% are generally accepted in the field and only “40% have generally favorable reviews of their psychometric and technical properties in authorities such as the Mental Measurements Yearbook”. The original ABC article notes that the two most common tests are the “Multiphasic Personality Inventory, which has generally positive reviews in the professional literature”, and the Rorschach inkblot test, which the study claims is heavily debated in the field as being too subjective. Firstly, the study did itself a service in casting a wide net, observing many techniques and almost two dozen surveys, as this lets them do a more comprehensive analysis which covers the wide array of psychological tests which could (and have) appeared in court. The fact that they base it on the Mental Measurements Yearbook also helps, as this bases their conclusions on the what people in the know generally agree upon.

Next, they performed “legal analysis of admissibility challenges with regard to psychological assessments”, looking at the screening of psychological tests in courts, how many are challenged, and how many challenges are successful. This part concludes that there are very few legal challenges to these tests, even though the results of part one indicate that a good portion of those tests are not agreed upon or even favorable. Challenges for any reason only occurred in “5.1% of cases in the sample”, and only half of that was due to questions of validity. Of those, it was found that challenged only “succeeded only about a third of the time”, meaning only about 1.7% of cases in the sample were successfully challenged. According to the study, “Attorneys rarely challenge psychological expert assessment evidence, and when they do, judges often fail to exercise the scrutiny required by law”. This means that despite the disagreements over the validity of some psychological tools, the proportion of challenges to these tools in courts is practically negligible.

In order to further assess the validity of the study, I tried to read laterally about the journal itself. Upon googling “Psychological Science in the Public Interest”, I found that according to Google, the journal, which is published triannually by SAGE publications on behalf of the APS, had an impact factor of 21.286 as of 2017. The Wikipedia entry for this journal matches this figure, citing it from the Journal Citation Reports publication by Clarivate Analytics, which gave the Psychological Science in the Public Interest journal the third highest impact factor in the “Psychology, Multidisciplinary” category. This is a promising sign, indicating that this journal is reputable. Searching google for discussions of this journal excluding the journal’s, APS’s, and SAGE’s input (the people who are involved in the journal), proved to be somewhat difficult, even using search syntax like “psychological science in the public interest -site:psychologicalscience.org -site:sagepub.com”. However, I was able to look at each of the co-authors of the study on Google Scholar to see how many citations they have and thus how involved/influential they are in their fields. Each one had thousands of citations (1110 for Neal, 9780 for Slobogin, 11283 for Saks, 4454 for Faigman, and 5214 for Geisinger). This establishes each of the authors as very active in their fields, meaning that they are much more likely to be experts. All in all, reading laterally shows that the authors of this study and the journal which published it are likely reliable.

In conclusion, this study seems pretty factual. It casts a wide net, does a wide analysis with the data it received which matches with the consensus of people in the know, and comes from a reputable journal with expert authors. Thus, the claim that courts are allowing unreliable psychological tests and junk science to be used as evidence is factually accurate.